As the Citrus Bowl is undergoing a much-needed major renovation, the new facilities could be a threat to historic Tinker Field. (Story) What would Orlando be losing by demolishing an old rundown stadium? This is a look at the history of one of the oldest Major League Baseball Spring Training stadiums left in United States and its link to Orlando’s baseball past.

The story of Tinker Feld starts with its namesake, Joe Tinker.

Joe Tinker

Two Orlando entries on the National Register of Historic Places bear his name: the Tinker Building on West Pine Street and Tinker Field on West Church Street.

Known for his baseball career from 1902 to 1916 with the Chicago Cubs and Cincinnati Reds, Joe Tinker was one of the early baseball greats. He earned his way to the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Retired from play by 1920, Tinker moved to Orlando. The climate here was better for his ailing wife. He remained working in baseball as the owner and manager of the Orlando Tigers (Florida State Baseball League). He led the team (nicknamed Tinker’s Tigers) to win the league championship in 1921 and take the championship trophy, the Temple Cup, away from rival Tampa Smokers.

The Tigers became the Orlando Bulldogs and Tinker was team general manager. Around this time he remained involved in Major League Baseball as a scout for the Cincinnati Reds. His affiliation with the Reds was key in their decision to bring spring training to Orlando in 1923.

Tinker took a break from baseball and focused on his real estate company. His Central Florida investments included the Longwood Hotel and an Orlando billiard parlor that was a popular spot for visiting baseball greats. After the repeal of prohibition, he opened one of the first places to order a legal drink in Orlando: Tinker’s Tavern on Wall St.

Joe Tinker’s Pine Street office building, built during the 1920’s, stands today with “Tinker” spelled out in decorative tile along the top. It was added the National Register of Historic Places in 1980. The Tinker Building has been renovated and well cared for over the years in a manner fitting for a local landmark. Unfortunately, Tinker Field has not enjoyed the same fate.

Tinker Field

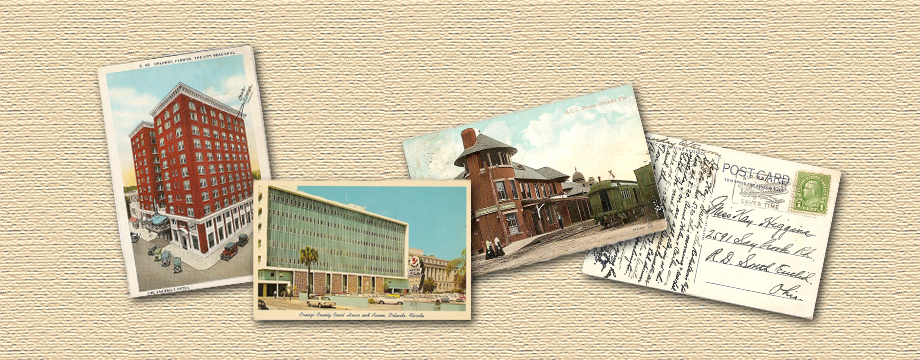

Orlando has played baseball where Tinker Field stands today since 1914. In 1923, a $50,000 1500-seat wooden stadium was dedicated on April 19th and named after Joe Tinker. Opening day tickets were sold at the cigar counters of the Angebilt Hotel and across the street at the San Juan Hotel. Prices were 85¢ for the grand stand and 55¢ to sit in the bleachers. Businesses closed and 1700 people turned out to see the Orlando Bulldogs defeat the Lakeland Highlanders 3 to 1 in their new state of the art stadium.

Most years between 1919 and 1972 Orlando had a baseball team in the Florida State League. The team names varied over the years, but won eight FSL Championships between 1919 (Orlando Caps were co-champions with the Sanford Celeryfeds) and 1968 (Orlando Twins).

Tinker Field’s real significance is as a spring training park. It is one of the oldest remaining spring training stadiums in the country and dates back to the era of Wrigley Field and Fenway park. An amazing list of baseball legends played here: Jackie Robinson, Hank Aaron, Joe DiMaggio, Lou Gehrig, Mickey Mantle, and Babe Ruth.

From 1923 until 1990, this was the spring break home a number of major league teams: Cincinnati Reds, Brooklyn Dodgers and for over 50 years the Washington Senators/Minnesota Twins.

(Link to a previous Orlando Retro post about the Minnesota Twins Spring Training in Orlando)

Tinker Field brought major league baseball to Orlando. The New York Times archive has many articles about the Dodgers training here in the thirties. For example, a 1935 New York Times article reported 2000 fans at a March spring training game. Fans saw Ken Strong from the New York Giants train with the Dodgers. (He didn’t make it out of spring training.) In 1949, a larger crowd of over 2400 paid tribute to baseball veterans Connie Mack (86 at the time) and Clark Griffith (79) before an exhibition game.

Even in recent years, the Orlando Monarchs called Tinker their home field.

Outside baseball, Tinker Field has been the scene of many community and entertainment events:

- 1928: an athletic charity event to benefit an African-American hospital

- 1935: 10,000 attended a barbecue honoring Florida Governor David Sholtz

- 1935: The Orlando Festival included 20 Central and South American countries participating in elaborate pageants for “the entertainment of Winter visitors”.

- Over the years, concerts from Marilyn Manson to the Beach Boys.

- 2011-2013: The venue for Electric Daisy Carnival Orlando, an electronic music festival.

Martin Luther King, Jr made his only Orlando appearance at a newly renovated Tinker Field in 1964 and spoke from the pitcher’s mound. In ’63, the wooden stadium was replaced with the larger stadium that stands today. Over 2000 people heard Dr. King speak that March day. It was at the height of the civil rights movement. The Orlando visit was only weeks before his St. Augustine arrest for protesting segregation. President Johnson signed the 1964 civil rights act in July of the same year.

In the last decade, maintenance was not kept up and it has been left to deteriorate. As the city builds and improves sports venues, Tinker Field should not be overlooked. A world-class basketball arena, planned improved Citrus Bowl, and new MLS soccer stadium are important to the city, but also important are our connections to our baseball past and community history. If the stadium is not saved, it would be a shame to lose Tinker Field without some significant tribute to this landmark.

Sources:

- New York Times: Mar 18, 1935, Apr 7, 1935, Feb 7, 1937, Apr 4, 1949

- Remembering Orlando, Tales From Elvis to Disney, Joy Wallace Dickinson, 2006

- Tinker, Evers, and Change: A Triple Biography, Gil Bogen, 2003

- Orlando, A Centennial History, Eve Bacon, 1975